The OECD has a new survey out of the Euro area economy, including some slides (slides) from Pier-Carlo Padoan:Among other things, you see here another illustration of the point that there’s something very simplistic about the “Germany has high net exports because we make good cars” theory of global trade flows. BMW made good cars in the 1990s, too, but Germany ran modest trade deficits at that point. And if Germans (and Dutch, Austrian, Swedish, etc.) households started buying more consumer goods (or, equivalently, taking more vacations) the growth outlook for neighboring countries would be better. But this wouldn’t just be a favor to the people of Spain, Germans would actually have more stuff. The Schröder government undertook a lot of politically difficult reforms in order to boost German productive capacity. But presumably the point of this was to actually reap more rapid increases in living standards and not just to try to win some kind of global exports championship.

Monday, December 13, 2010

Yglesias » Evolution of Eurozone Trade Balance

China’s Army of Graduates Faces Struggle - NYTimes.com

In a kind of cruel reversal, China’s old migrant class — uneducated villagers who flocked to factory towns to make goods for export — are now in high demand, with spot labor shortages and tighter government oversight driving up blue-collar wages.

But the supply of those trained in accounting, finance and computer programming now seems limitless, and their value has plunged. Between 2003 and 2009, the average starting salary for migrant laborers grew by nearly 80 percent; during the same period, starting pay for college graduates stayed the same, although their wages actually decreased if inflation is taken into account.

Saturday, December 11, 2010

Who Exports

talking about the balance of trade with Germans. One thing you often hear from Germans on this issue is a kind of patronizing line about “oh, are you saying we should make our products worse? If America has a trade balance problem, you guys should make better stuff!

...This whole line of thought seems to me to be largely based around confusing exports with net exports. If you just look at aggregate exports then Germany and the United States are very closely packed. There’s only slightly more German-made stuff being purchased by non-Germans than there is American-made stuff being purchased by non-Americans. And if you look at adjacent countries, the combined GDP of Poland + Czech Republic + Austria + Switzerland + France + Belgium + Netherlands + Luxembourg + Denmark is wildly higher than Mexico + Canada. Indeed, France alone has a bigger economy than Canada and Mexico combined. Or to look at it in the most clear-cut way, the per capita output of the American economy is higher than the per capita output of Germany, whether measured at market exchange rates or with PPP adjustments.

Long story short, the issue here really and truly is one of German households engaging in a very high rate of savings and not one of Germany firms being somehow extra awesome at making desirable products. German firms are great, the German people make a lot of stuff, and on a per hour basis the German workforce is incredibly productive. And good for them! But they’re not actually not outproducing the United States of America, they’re buying less stuff. Which would be fine if when the world turned around to look at what’s happening with these savings we saw the world’s finest banking system financing highly productive investments all ’round the world. But is that actually what we see? I see German banks financing bum real estate developments in Ireland, Nevada, Spain, Florida, etc. ...The issue of the questionable prudence of the savers is a real one here. If I heard more people saying with a straight face “Matt, the reason our households save so much is our banks are uniquely skilled at channeling savings into profitable investments” I’d feel much happier about the whole thing.

Monday, December 6, 2010

Trade Does Not Equal Jobs - NYTimes.com

One thing I’m hearing, now that all hope of useful fiscal policy is gone, is the idea that trade can be a driver of recovery — that stuff like the South Korea trade agreement can serve as a form of macro policy.

Um, no.

Our macro problem is insufficient spending on U.S.-produced goods and services; this spending is defined by

Y = C + I + G + X – M

where C is consumer spending, I investment spending, G government purchases of goods and services, X is exports, and M is imports. Trade agreements raise X — but they also lead to higher M. On average, they’re a wash.

This, by the way, is why claims that the Smoot-Hawley tariff caused the Great Depression are nonsense. Yes, protectionism reduced world exports; it also reduced world imports, by the same amount.

There is a case for freer trade — it may make the world economy more efficient. But it does nothing to increase demand.

And there’s even an argument to the effect that increased trade reduces US employment in the current context; if the jobs we gain are higher value-added per worker, while those we lose are lower value-added, and spending stays the same, that means the same GDP but fewer jobs.

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

Robotic Warriors and Industrial Policy

Perhaps the most disturbing truth is that a book about military applications of robotics is largely coextensive with a book about robotics in the United States. Singer alludes to the fact that the world leader in robotics is Japan, where technological prowess is used to do productive work on behalf of a skilled but aging population. There robots are “used for everything from farming and construction to nursing and elder care” in a country that contains “about a third of all the world’s industrial robots.” In the U.S., by contrast, civilian applications of robots remain relatively primitive. The field is dominated by defense-oriented research funding and competition for large defense-related government contracts. Perhaps the most notable American civilian robot is the Roomba, a sort of semi-intelligent vacuum cleaner. But even this is made by a firm, iRobot, that has extensive defense contracts for its PackBot and other military robots.Yglesias » Robotic Warriors:

Shunting such a large proportion of our talented engineers into dreaming up more clever ways to engage in misguided military adventures seems to me to be a policy that’s going to end up leaving a lot of useful ideas on the table. If you took the funds currently appropriated for specialized high-tech defense procurement and put some of them into basic research funding and gave some of them back to the private sector, we’d be on the road to higher productivity.

Chinese 'Button Town' Struggles with Success : NPR

Look down at the shirt you're wearing. Chances are the buttons came from Qiaotou. The small Chinese town, with about 200 factories and 20,000 migrant workers, produces 60 percent of the world's supply.

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Wall Street, investment bankers, and social good : The New Yorker

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Swan Songs - NYTimes.com

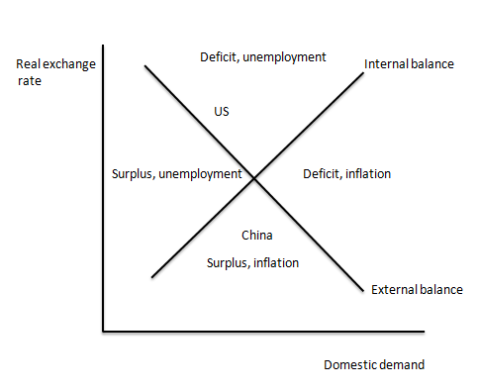

The best way to think about this sort of thing remains the Swan diagram, a half-century-old creation of the Australian economist Trevor Swan. He pointed out that, at minimum, economic policy has two instruments and two goals: the exchange rate and measures that affect domestic demand, on one side, and a sustainable balance of payments position and full employment without inflation, on the other. He then argued that you can usefully look at the state of an economy to get some idea of which policies are out of line — but that it’s not as simple as saying that a trade deficit means you need to devalue, or unemployment means you need more demand. Instead, the “zones of economic happinessunhappiness” are delineated as shown:

And I have, as you see, written in two major economies. Clearly — clearly! — China has an undervalued currency; you can tell this not simply from the fact that it has a trade surplus, but from the fact that it’s fighting inflation. The United States, which is fighting unemployment while suffering a large trade deficit, is in exactly the opposite situation — which is why it’s ludicrous to suggest that US QE and Chinese currency manipulation are equivalent.

And now China is considering price controls to help it maintain its undervalued currency. Bizarre, and disastrous for all of us.

Unsubstantiated Claims « Modeled Behavior

Unsubstantiated Claims « Modeled Behavior:

...the Fed for good reasons does not have a mandate to maintain a strong dollar. I wish I could devote more time to this. My wife says that we could clear up a lot of confusion by replacing strong dollar/weak dollar with fat dollar/skinny dollar. Then we could just say that the dollar is morbidly obese and millions of Americans would immediately think it a moral imperative to make the dollar lose weight.

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Yglesias » The Generalized System of Preferences

America’s habit of charging tariffs on imported textiles is particularly egregious. Clothing represents a larger share of consumption for poor people than for the rich. Consequently, I think most people understand that if I were to propose a special sales tax on clothing it would be an unusually regressive tax measure. By levying the special tales tax exclusively on foreign-made clothing we don’t eliminate the negative impact on poor Americans. We do, however, shift around who benefits. By taxing only foreign-made clothing, government revenue (which at least finances many programs that are important to poor people) declines and instead many of the benefits are captured by the owners and managers of US-based textile firms. To make things even worse, politically powerful well-heeled people have generally managed to make it the case that luxury goods are taxed more lightly than things ordinary folks buy.

Long story short, dropping tariffs on imported textiles is one of the easiest and most effective things we could do to help poor Americans while also improving the prospects for economic growth in the third world.

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Yglesias » Home Page

China accounts for much more than 20 percent of total trade-related media coverage, even though the PRC is just 18.5 percent of our imports and less than 17 percent of our total trade. By contrast Canada is systematically under-covered in the American media. This is especially true when you consider that Canada-based business establishments are much more likely to be directly competing with US-based ones.

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

Matthew Yglesias » A Land Where Charity Is Illegal

But an overriding reason explains why charity barely exists in contemporary China: The Communist Party makes giving difficult. Why? The Party wants no competitors, especially organized ones. Charities, therefore, have to find government sponsors before they can register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs, and this requirement severely limits the number of them. Even Hollywood action star Jet Li, a favorite of Beijing because he makes “patriotic” films, cannot register his One Foundation, which may have to suspend operations soon.

Don’t be surprised that as of last year there were, in all of China, only 643 foundations not run by the government. There were an estimated 300,000 so-called grassroots organizations that were operating without registering, or had registered as business enterprises.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

Outdated Tariff Systems Means the Poor Pay More « The Washington Independent

low-income Americans end up paying extra for necessities like clothes and shoes — victims of an outdated, inefficient tariff system that inadvertently penalizes the poor. Even proponents of reform, though, acknowledge that the byzantine nature of the tariff code and the low priority it’s generally assigned by lawmakers makes the prospect of changing this entrenched system unlikely.

Luxury goods have very low tariffs, while cheap clothes, underwear, shoes and household products have much higher rates, said Edward Gresser, trade policy director at the Democratic Leadership Council. “The people who are paying for the tariff system don’t know they’re paying for it,” he said.

“It’s the dirty secret of the U.S. tariff code,” said Daniel Griswold, trade policy expert at the Cato Institute. “It’s our most regressive tax that the federal government imposes.” ...The disparities are staggering. In his research, Gresser found that the tariff rate on a cashmere sweater is 4 percent; the rate for one made of much cheaper acrylic is 32 percent. A silk brassiere has a tariff rate of less than 3 percent, but the rate on a polyester one is slightly less than 17 percent. The tariff rate on a snakeskin handbag is just over 5 percent but climbs to 16 percent for one made of canvas. Similar variations occur when it comes to household goods. Drinking glasses that cost more than $5 each have a tariff of 3 percent, while those that cost less than 30 cents each have a rate of 28.5 percent. A silk pillowcase has a rate of 4.5 percent; this goes up to nearly 15 percent for one made of polyester.

Overall, clothes and shoes contributed nearly $10 billion in tariff revenue in 2009, while higher-cost items including audiovisual equipment, computers and even cars added less than $2 billion. Gresser contends that the $10 billion is disproportionately borne by people who can’t afford to buy luxury goods.

Globalization has had a similar incidence in labor markets. It has adversely impacted the lowest-wage manufacturing workers and benefited the highest wage people in finance who have been able to sell financial products all over the globe. Whereas highly paid doctors have little competition from globalization, low wage jobs get much more competition from foreign workers (such as via immigration).

Economic Scene - The Long View of Changes in China’s Currency - NYTimes.com

"a stronger renminbi would not be a quick fix for our economic problems, as appealing a notion as that might be... The renminbi itself rose 21 percent against the dollar from 2005 to 2008, and the trade deficit continued to widen.Also see the graph of the yuan exchange rate. It fell dramatically in the 80s and 90s and then remained fixed with occasional small adjustments. Also see Paul Krugman's takedown of the Chinese notion that their exchange rate doesn't matter.But there is also no question that China’s currency remains undervalued, probably by 20 percent or so. The economics are simple enough. The huge demand for Chinese goods should be driving up the price of its currency, but Beijing has been intervening to prevent that. Getting China to stop will be crucial to correcting the global economy’s imbalances. A stronger renminbi will help China’s people — many of whom are hungry for better living standards, to judge by the recent labor strikes — buy more goods and services, and it will also help the rest of world produce more. But change is not going to happen overnight.

...Chinese officials sometimes go so far as to suggest that the value of the renminbi makes little difference. That’s wrong. ...economies, like battleships, tend to turn slowly. Companies rarely move production in a matter of weeks. If they are using a Chinese supplier, it is often cheaper to stick with that supplier for a while, even if costs rise, rather than find a new one in another country.

Monday, August 30, 2010

Random Density Facts

To reach for a policy point here, the Texas/Jersey thing illustrates that it would be possible for the United States to contain a lot more wilderness without jamming everyone into super-dense cities. New Jersey is the quintessential suburban state.

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Have we underestimated Chinese consumption?

How do we know that China has an under-consumption problem? To answer that question it is unnecessary even to look at the consumption statistics. All you need to know is that China has a very high investment rate (perhaps the highest in the world) and a huge trade surplus.

Every country produces goods and either consumes or invests those goods. This is not quite an accounting identity, but it becomes one if you take into account the trade balance. Why? Because if it produces more than it consumes or invests, it must run a trade surplus. If it produces less, it must run a trade deficit. In other words by definition what ever you produce is equal to what you invest plus what you consume plus or minus the trade balance.

China has an extremely high investment rate, perhaps the highest ever recorded for a medium or large economy. Countries with high investment rates should normally run trade deficits, since there is so little left over of their production for them to consume that they must import the balance. This is what happened, for example, to the US during most of the 19th Century.

But China has probably the highest trade surplus ever recorded. This means that an extraordinarily large portion of its production is invested, and another extraordinarily large portion is exported. So what about consumption? The only way a country can run an extraordinarily high investment rate and an extraordinarily high trade surplus is if consumption is extraordinarily low.

So almsot by definition we know that consumption in China is extraordinarily low as a share of its total production. It is unnecessary to check consumption statistics to prove this.

In fact official statistics do prove it. They show that Chinese households consumed a little less than 36% of total GDP last year. This is an unprecedented number, much lower than the 65-70% typical of the US and Europe and even far below the 50-55% typical of other low-consuming Asian countries.

...Credit Suisse estimates that last year Chinese household consumption was just over 31 percent of GDP – although I am not sure even they completely believe this number. Still, it suggests that the real consumption rate may be between 31% (their number) and 36% (the official number). Either number is completely off the charts.

So isn’t this good news for consumption as far as its implications foe the economic imbalances? Consumption is so low that it has no choice but to surge, right? Perhaps, but I am very uncomfortable with this argument. It seems to me that the only way consumption can be so low is if there are some very severe structural impediments that distort consumption growth, and I think there is no reason simply to assume or hope that these impediments will dissolve and, as they do, consumption will explode. Rather than proclaim that Professor Wang’s adjusted consumption rate is more evidence that consumption must surge, it seems more reasonable to wonder how any country can have such a massive imbalance. And how can Beijing unwind this imbalance?

Chinese consumption and the Japanese Model

China Financial Markets: "in order to rebalance the economy China must sharply raise the consumption share of GDP. It has declined from 46% of GDP in 2000, which was already a very low number, although not quite unprecedented, to 41% in 2003, which is, I believe, an unprecedented number, at least for any large economy.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Consumption declined further as a share of GDP to an astonishing 38% in 2006, finally to end under 36% in 2009. I don’t think we have ever seen anything close to this level before.

... In order to get to 47% of GDP in ten years, consumption needs to do something it has never been able to do – grow faster than GDP by a huge margin – something like three full percentage points – every year for the next ten years.

...If China continues growing at 7-9% for the next decade, which is what many analysts seem to be projecting (very unlikely, I say), consumption must grow much faster than it ever has in post-reform Chinese history, even while China’s GDP grows more slowly than it ever has during that period.It’s arithmetically possible, of course, but there are two schools of thought about how to do it. One school argues that relatively low consumption growth has to do with factors that can be changed without changing the fundamental growth model – perhaps demographics, or Confucian culture, or tax incentives, or lack of TV advertising, or the sex imbalance, or the lack of a social safety net, etc.

If they are right, then presumably Beijing can administratively address those issues while separately keeping GDP growth rates high. But if that’s what it takes, and since they have been determined since 2005-06 to drive up the consumption share of GDP, and during that time it has plummeted, you sort of wonder why they just don’t get on with it.

The other much smaller school (but growing rapidly, I think) argues that low consumption is a fundamental feature of the growth model because of the hidden taxes that channel household income into subsidizing growth. Growth is high, in other words, because consumption is low. This group has been arguing for the past five years that all the measures Beijing has taken to ensure more rapid consumption growth will fail because they do not address the underlying cause.

I guess we will just have to wait and see who is right, but I am confident enough to say that unless GDP growth plummets to below 5% annually on average, and probably even then, there is no way consumption will represent 47% of GDP in ten years. I say this with one caveat – if Beijing were to engineer a huge shift of state wealth to the household sector, say in a massive privatization program, it could boost household consumption significantly, but I suspect that this will be politically difficult to do.

...So why do they consume such a low share of national GDP – perhaps the lowest share ever recorded? The answer has to do with the level of household income as a share of GDP, also one of the lowest ever recorded.

Chinese households are happy to consume, but they own such a small share of total national income that their consumption is necessarily also a small share of national income. And just as the household share of national income has declined dramatically in the past decade, so has household consumption. This isn’t to say households are getting poorer. On the contrary, they are getting richer, but they are getting richer at a much slower speed than the country overall, which means their share of total income is declining.

... The Chinese development model is mostly a souped-up version of the Asian development model, and shares fundamental features with Brazil during the “miracle” years of the 1960s and 1970. While it can generate tremendous growth early on, it also leads inexorably to deep imbalances.

At the heart of the model are subsidies for manufacturing and investment paid for by households. In some cases, as with Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s, the household costs are explicit – Brazil taxed household income heavily and invested the proceeds in manufacturing and infrastructure. The Asian variety relies on less explicit mechanisms to accomplish the same purpose. It channels wealth away from the household sector and uses it to subsidize growth by restraining wages, undervaluing the currency, and keeping the cost of capital extremely low.

This model, which some also refer to as the Japanese model, and which many countries have followed before China, has been extraordinarily successful in generating eye-popping rates of growth, but it always eventually runs into the same constraints: massive overinvestment and misallocated capital. And in every case I can think of it has been very difficult to change the growth model because too much of the economy depends on hidden subsidies to survive.

...Japan itself provides the most worrying example. It kept boosting investment to generate high growth well into the early 1990s, long after the true economic value of its investment had turned negative.

But for a long time the problem of misallocated investment, which was whispered about in Japan but not taken too seriously, didn’t seem to matter. After all, as nearly everyone knew, Japan’s leaders were extremely smart, with a deep knowledge of the very special circumstances that made Japan different from other countries and not subject to “western” economic laws, with real control over the economy, with a strong grasp of history and penchant for long-term thinking, and most of all with a clear understanding of what was needed to fix Japan’s problems.